Swedish Death Cleaning

I grieve for everything these days: Mom's barely used glasses, the time we think we have.

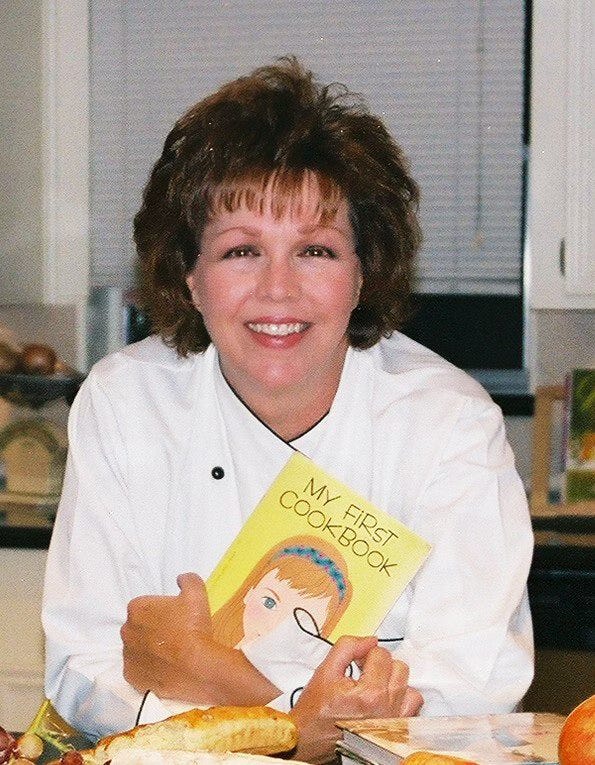

I have lost count of the ramekins. Boxes of ramekins in every color. Some are your bog standard white catering ramekins. Some are lime green and teal Le Creuset ramekins. Some are in boxes. Some are rattling around like loose cigarettes sold on a street corner. All are pouring out of a guest room closet upstairs where my mother has long stored her personal chef supplies. Mom retired from being a personal chef last year but before she did, she catered countless parties and events over the decades. I even helped her with some of them, which is where I learned that I am terrible at wrapping spring rolls — even with plenty of practice my clumsy fingers perpetually tore through the delicate rice paper — and terrific at passing apps.

Mom is still very much alive in her bedroom downstairs as my cousin Jennifer and stepbrother Eric are cleaning out this one of many closets. Like the adjacent guest bedroom that acted as a default Hobby Lobby for seasonal decor, Mom has been clear about her wishes for the things in these rooms and where they should go. The decor to her ladies Bible class at church; the chef stuff to her friends who are still cheffing professionally. For them, we have nigh-endless shelves of chafing dishes and serving plates and wine glasses and wine chillers and cheese knives and chargers to choose from. But first we have to clean it all out.

Jennifer has tackled the bulk of it, the most naturally organized of all the family members, and from the back of the closet she pulls something unrelated to cheffing: a collection of photographs framed, vintage style, in one giant collage. Some of them have mysteriously disappeared but most are still intact; all of them are of my stepbrothers in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

“Look how little you were!” Jennifer says, pointing to a 13-year-old Eric.

Eric, whose nickname as an adult is Fatboy, chuckles. “Look how skinny I was!” He points to another photo of himself alongside some young men I don’t recognize. “That’s Troy,” he says about one tow-headed teenager. “He’s dead now.”

Troy, Eric explains, was one of the first victims of Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Sitting in his apartment as the Addicks Dam was released and its floodwaters came rushing into every home in its West Houston path, Troy figured he’d decamp to his giant 4X4 pick-up truck outside. The floodwaters, he thought, couldn’t possibly reach as high as his cab. So he turned on the engine, cranked the A/C and fell asleep. Troy never woke up. The waters reached his tailpipe before they reached his cab. The carbon monoxide exhaust that could no longer escape was instead redirected inside his car, where Troy peacefully passed away in his sleep, none the wiser.

“So weird the ways people die,” Eric says. “Things you could never expect in a million years.”

None of us expected Mom would go like this either. The suddenness of it. The fact that she was otherwise as healthy as a horse until her December diagnosis. The woman almost never even got sick. I can hardly remember her even having a cold. Later that night, looking at old photos of her from the 1980s, I’m suddenly hit with another deep wave of grief.

“It went so fast,” I tell my husband between heavy sobs. “Forty-four years. They went so fast. Just a finger snap. I only got to have her for 44 years.”

She just got a new pair of glasses. She was so excited about them. They’ve been sitting on her bedside table basically unused. I grieve for everything these days: her barely used glasses, the time we think we have.

One of the peculiar forms of anticipatory grief I’ve been experiencing lately is knowing that I only have a few more days or possibly weeks with Mom but not knowing what to say when I’m there with her. It’s so hard for her to talk right now, so I don’t want to pepper her with questions, but I also don’t know what to say when I’m sitting there with her other than “I love you, I love you, I love you.” It doesn’t seem like enough.

“Why can’t I think of anything to say?” I sob. “I don’t have much time left and I can’t think of anything substantive to say to her. My brain is just broken.”

“I think, knowing your mom, that just being there with her is enough,” John says.

A few days ago sitting at Mom’s bedside, she told me she wished I were still a baby.

“I wish you were eight pounds again and I could just hold you here with me all day,” she said.

Looking at pictures of her holding me as a baby, we both look so comfortable. She looks like she was born to the role of mother. I look so happy and content. She loved being a mother. She loved having me. I loved having her.

This is not to gloss over the hard times, of course. I don’t think any mother-daughter relationship is all sunshine and roses. When we were clearing out my grandmother’s house in 2014 to move her down to Houston from Dallas, where she spent her final years in a fancy retirement village that was still a far cry from her own sprawling home in Lake Highlands, my mother fussed and stressed over how every single closet in Meemo’s house was filled with stuff. The two of them tangled over nearly every object that had been squirreled away since Meemo and Granddaddy moved into the house in 1978.

“How do you have so much stuff?” Mom asked her repeatedly, exasperated. “I’ll never do this to you, Katie,” she said.

Meemo, for her part, was equally exasperated at having to pare down her beloved treasure trove of carefully curated lamps and tastefully upholstered sofas and heavy Oriental rugs to move into a one-bedroom apartment that barely had room for her to plant a garden outside. And Meemo — like her daughter — loved a garden. Mom and Meemo tussled about everything, down to the color of Meemo’s bedspread when they were making her bed in the new apartment. Mom said it was blue. Meemo said it was green. I got them both to eventually agree the bedspread was aqua.

Now here we are, 11 years later, and Mom has stuffed every one of her own closets as full as Meemo’s once were. You have to laugh at the irony, I tell Jennifer as we open another closet to find it entirely filled with Christmas decorations and canned food.

“I thought I cleaned out all the expired canned food in the pantry, and that took me two days!” she said.

“Have you ever heard of Swedish death cleaning?” I asked her.

“No, what’s that?”

The concept is this: döstädning is the process of organizing and decluttering your home before you die, ideally to lessen the burden on your loved ones after you’ve passed on. In Sweden, older people or folks with a terminal illness typically embark on this cleaning journey as a way of taking stock of their life while deciding what things are important enough to be saved and passed to someone else. Everything else gets given away, donated, recycled, etc. A popular 2017 book by Margareta Magnussen, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter, transported the idea from its native Sweden to other countries, where it attracted the same sort of attention as Marie Kondo’s KonMari method of only keeping things that “spark joy.”

My mother, of course, declined too quickly to partake in any Swedish death cleaning, but I don’t know that she would have been an advocate of the method regardless. Accruing items was comforting to her. She enjoyed being a living Hobby Lobby so she could make intricate tablescapes and centerpieces for the women at her church luncheons; this is how she showed her love. She loved having a hoard of ramekins in case the time ever came when someone needed 86 of them. She took solace in knowing that, should something horrifying ever happen in the world outside their house, she and Ralph would have enough canned and dried food to keep them going at least as long as the propane fueling their whole-house generator lasted.

“She was certainly not a minimalist,” my stepbrother laughs as we tackle another closet. Eric says he understands her. “Hell, I was only a minimalist while I was in prison. Once I got out, I went full maximalist too.”

And just as Mom’s stuff brought her comfort in life, it’s bringing her comfort as she passes in the knowledge that much of it will go to people who will love and cherish and use it much as she did. Swedish death cleaning, in a sense, just down to the wire. Rita will take some of the ramekins. The Ukrainian refugees she’s worked with so tirelessly at church will take her many, many, many extra plates and platters and glasses. I will take and wear my mother’s chefs coats with her name proudly embroidered them. I will think of her every time I wear them. I will think of how happy she was to wear them to work every day. I will think of how she provided so much for us over the years.

Maybe that’s what I’ll tell her next time I’m sitting next to her bed. How much I’ve loved being her daughter. How much I will think of her constantly, every day, from moment to moment, for as long or as short as I have left on this earth.